Inflation on the Brain: What Should Be Top of Mind?

• 5 min read

Get the latest in Research & Insights

Sign up to receive a weekly email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.

Americans have seen price increases across a number of product categories in recent months, for example in autos and recreational equipment, and will likely experience similar spikes in coming months, but these will probably be short-lived as factories ramp up production and the ransacked service sector fully reopens its doors.

“It should be smooth sailing for the next 12 to 18 months,” AMG chairman Earl Wright told clients during an April 29 webinar. Click here to watch the presentation. “But there are some things that we are watching … things to be concerned about.”

One such concern is the increased potential for runaway inflation sometime after the economy fully recovers in mid-2022.

But for now, outside of short-term price hikes, the U.S. economic outlook is sunny. GDP could be 6% or higher this year thanks to an increasingly successful COVID-19 vaccination campaign and a massive transfusion of federal spending intended to resuscitate American businesses smothered by the pandemic.

AMG generally recommends to clients tilting portfolios toward value stocks in developed foreign markets. During the recovery, these investments have the potential to continue to outpace growth stocks, which were big winners from the pandemic period.

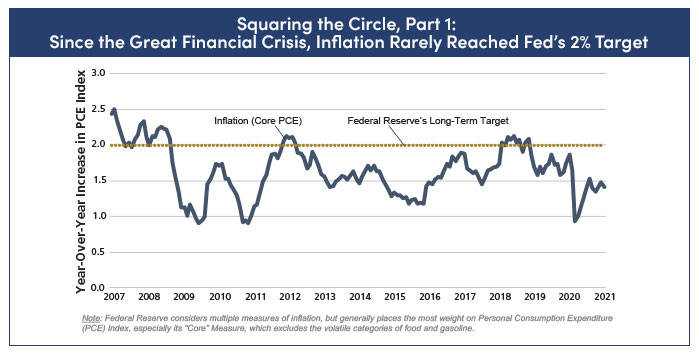

But the specter of inflation above 2%, which hasn’t reared its ugly head for 15 years, may bubble up in the longer term, according to Alex Musatov, AMG’s global research economist. Both manufacturing and service firms are increasingly reporting rising input costs. Industrial commodities are one example of such input costs, with one index showing 30% price increases since last July. Freight costs are also jumping, particularly for transoceanic shipping where prices have tripled in the past 12 months to reach historic highs.

Yet, judging from recent statements from Federal Reserve (FED) policymakers, accelerating inflation is hardly on their radar, Musatov pointed out, noting recent statements by Mary Daly, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, who said “We are not hitting our inflation target (2% annually) right now. We are expecting temporary increases in inflation, but those will go back as soon as they roll through the 12-month COVID-19 math. And we still have almost 10 million people on the sidelines looking for jobs.”

The Fed faces four potential crosswinds that could fan that inflation:

- Consumers are sitting on hefty savings—over $1 trillion. Normally, U.S. household savings are 7% of disposable income, but recently they have been as high as 14%, which could trigger an unexpected spike in demand as people are vaccinated and return to normal activities.

- U.S. monetary policy remains ultra-accommodative, meaning interest rates are historically low and the economy is awash in cash, as the Fed tries to restore the economy’s health back to pre-pandemic levels.

- The federal deficit has expanded rapidly as lawmakers have tried to soften the economic blow of last year’s sharp COVID-19-induced recession and help businesses and workers alike recover. The federal deficit in 2020 grew to an estimated $3.1 trillion and could be even higher this year, depending on several recovery programs now before Congress.

- Global supply chains are not fully mended from last year’s economic shutdown and recession. Trade has helped to keep inflation mostly in check for decades across the globe, but the pandemic has disrupted some of the trade channels that have delivered the least expensive goods to where they are most needed.

- Concerned investors should also keep in mind two axioms. First, there is no direct link between deficit spending and inflation. Second, inflation can be a self-fulfilling prophesy; if consumers believe prices will go up, they tend to bring about inflation through their actions.

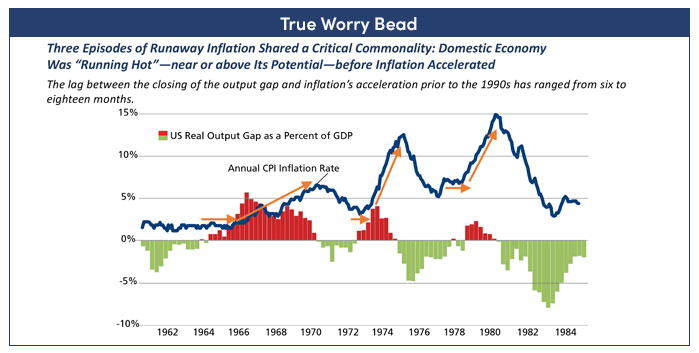

“Inflation is caused by too much money chasing too few goods and services,” said Dr. Michael Bergmann, AMG’s chief economist, explaining that runaway inflation usually occurs when an economy runs too hot, which is further exacerbated by bad economic-policy decisions and/or unforeseen external events.

He pointed to the last few times the United States dealt with runaway inflation. In 1969, the annual change in Consumer Price Index (CPI) hit 6.2% after years of accelerating deficit spending as the country fought a war in Vietnam and a war on poverty at home. In December 1974, inflation peaked at 12.3% after several years of government-imposed wage and price controls and a Mid-East oil embargo caused barrel prices to more than triple. In March 1980, inflation topped out at 14.3% after the 1979 Iranian Revolution caused a drop in oil production, sparking another crisis as prices doubled.

Each of these inflationary episodes, Bergmann explained, came after the U.S. economy began to run hot, meaning the total demand for goods and services was so strong that it pushed total economic output (GDP) materially above its sustainable level (potential GDP). The difference between an economy’s economic output and its potential economic output is also known as its output gap.

Right now, the economy is accelerating but not running hot—some output gap still remains.

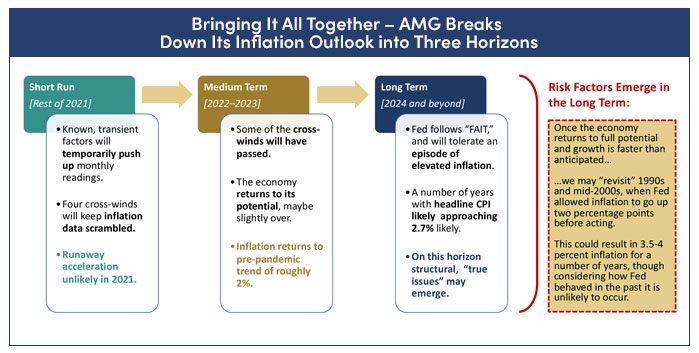

“Economic activity has made great strides over the past nine months and accelerated further during March,” AMG’s Musatov said, “but some slack remains to be burned off. Estimates of when this might occur vary as the pandemic can still reassert itself, but we presently expect the middle of 2022 to be the most likely timing.”

That’s when the real risk of accelerating inflation begins, he said, “when the economy returns to its full potential and growth is faster than anticipated.”

Markets are anticipating some surges in inflation in coming months as the economy accelerates, said Josh Stevens, senior vice president, AMG Capital Management, but AMG views inflation as drifting down near the Fed’s target level sometime in 2022.

He said corporate earnings have room to move substantially higher in the coming months and are likely to catch up to their long-term trend level about the time the output gap closes next year. He noted that President Biden’s tax plan may be implemented in 2022, but the S&P 500’s operating profits would still move higher, despite the tax hit, until well after the output gap had closed.

This information is for general information use only. It is not tailored to any specific situation, is not intended to be investment, tax, financial, legal, or other advice and should not be relied on as such. AMG’s opinions are subject to change without notice, and this report may not be updated to reflect changes in opinion. Forecasts, estimates, and certain other information contained herein are based on proprietary research and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any particular security, strategy, or investment product.