U.S. Debt & Deficits After COVID-19

• 11 min read

Get the latest in Research & Insights

Sign up to receive a weekly email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.

Specter of Inflation: Soaring federal debts raise concerns about reliving the economic turmoil of 50 years ago

WEBINAR SUMMARY: U.S. DEBT & DEFICITS AFTER COVID-19

Runaway inflation and interest rates are an unlikely result of the historic public debt being run up by the U.S. government to combat the COVID-19-induced economic recession.

But it could happen. It has before.

So in a few years, if our political leaders aren’t careful, it could be deju vu all over again as Americans relive turbulent economic times last seen a half century ago.

“This reminds me an awful lot of the 1970s,” said AMG National Trust Chairman Earl Wright during the July 9 COVID-19 Briefing webinar. Click here to watch the presentation.

“It seems like we’ve been there before,” added Dr. Michael Bergmann, AMG’s co-founder and economist, referring to the decade marked by economic stagnation, high interest rates, financial repression and rampant inflation – better known as stagflation. “Seen it. Done it. Not our first rodeo.”

Bergmann said that although the nation’s mounting deficit is a cause for watchful concern, it is not an immediate threat as America continues dealing with the pandemic and recession.

The news this month is mostly positive:

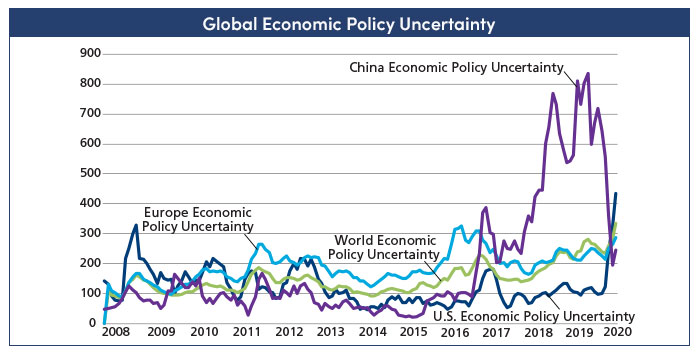

- The world economy appears to have started a recovery, and financial markets continue to climb in response. However, economic uncertainty in the United States outpaces the world, mainly because of the upcoming presidential election and fears of another lockdown due to an infection surge.

- Despite new infection hotspots, mainly in sunbelt states, death rates are relatively low, and most hospitals have not been overwhelmed with patients. Three of those states, California, Texas and Florida account for 30% of U.S. economic output, and the slowdown in their reopening is dampening the overall U.S. recovery.

- AMG’s base case for recovery remains unchanged with a return to pre-pandemic economic activity expected by the end of 2021 or early 2022. “Reopening and recovery of the economy are likely to take a long time, longer than markets initially thought … one to two years out … that lends itself to having a blended global equity portfolio,” said Josh Stevens, Senior Vice President – AMG Capital Management.

- The vaccine quest is on pace to develop, test, manufacture and distribute a safe and effective inoculation by early 2021. Six companies working on vaccines are receiving U.S. government funding, through Operation Warp Speed, to accelerate the process. Emergency doses could be available by the end of this year.

Until a vaccine is widely available, governments and central banks around the world will likely continue to infuse their economies with cash to keep their nascent recoveries humming.

RECENT EXPANSIVE MONETARY AND FISCAL POLICIES EXPAND PUBLIC DEBT

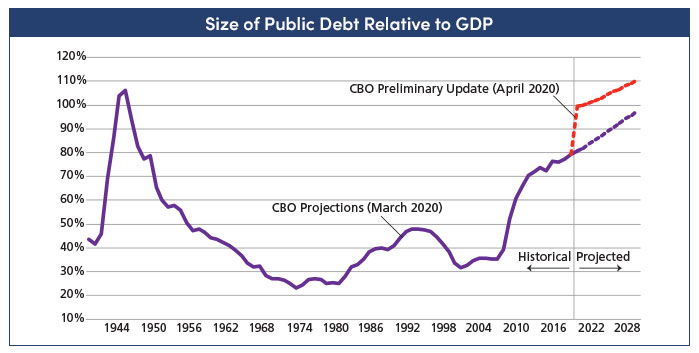

The United States has pumped about $6.2 trillion into the economy since March, an unprecedented amount that has raised the national debt to levels not seen since WWII. For many, this raises the twin specter of runaway inflation and interest rates last witnessed in the 1970s.

“Extraordinary expansive monetary and fiscal policies have been put in place in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic to promote eventual recovery,” said Bergmann “So, does that create a problem?

“Well, not right now, but there is an outside chance of a fiscal and monetary hangover down the road.”

Here’s how it happens.

The year 2024 is key, according to Bergmann:

“To avoid runaway inflation,” he said, “the Federal Reserve (Fed) must by then bring the expansion of the money supply under control. That means tightening monetary policy, which likely means raising interest rates.

“The problem is that politicians often have other immediate priorities than paying interest on the public debt, and so oppose monetary tightening.”

Here’s the nation’s situation right now. The public debt is exploding.

Since the end of February, the Fed has flooded credit markets with $2.8 trillion through its normal operations to ensure liquidity. The federal government has pumped another $2.4 trillion into the economy through four COVID-19 fiscal relief programs.

And both wings of government are not done. While lawmakers are debating additional relief payments to taxpayers, workers and businesses, the Fed’s special lending programs (so-called section 13(3) programs) are just getting underway. They have an announced potential capacity of another $2.6 trillion but actually could go even higher as some are not capped.

But suppose the Fed utilizes the announced capacity and makes no other asset purchases by year end 2021. In that case, the Fed’s portfolio would reach nearly $9.5 trillion—more than twice its level in late 2014 after the conclusion of three explicit quantitative-easing programs following the 2009 financial crisis and ensuing recession.

The ratio of federal debt-to-GDP right now is expected within a few years to exceed the one brought about by World War II. In 1946, the U.S. public debt was 106% of GDP.

But still, this massive spending effort probably will not lead to excessive inflation for several reasons:

- Highly expansionary policies are a response to temporary conditions; they won’t continue indefinitely.

- Consumers will likely be cautious in resuming spending patterns as the economy recovers.

- Productivity will pick up as suppression of economic activity is lifted.

- Even moderate shifts in monetary policy will slow money supply growth.

- Low inflation expectations will buy time for gradual policy shifts.

But what if a worst-case scenario unfolds through policy missteps or just plain bad luck?

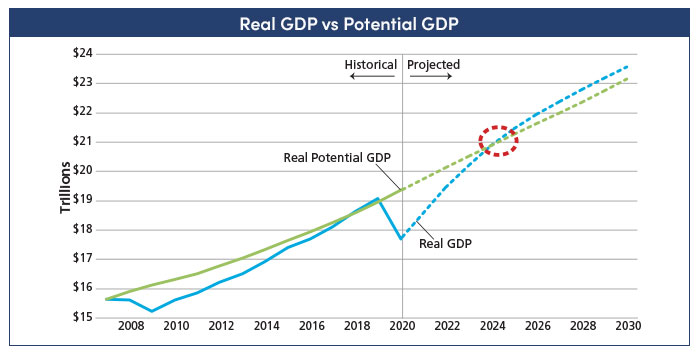

In order to generate inflation, money needs to be spent, and it needs to be spent on goods and services that can’t be supplied in quantities great enough to meet demand at current prices. Currently, demand is being suppressed more than supply, and as the economy opens up it’s probable that the total capacity of the economy will exceed demand.

However, actual production (real GDP) will eventually catch up to capacity (potential GDP).

As the graph above illustrates, given the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate for potential real GDP and AMG’s current projection for growth of real GDP, that probably would not occur before 2024.

To avoid runaway inflation, the Fed must, by then, bring the expansion of the money supply under control, which inevitably means raising interest rates. But politicians might not see that as a priority as they seek to keep taxes low and not cut the federal budget.

Currently, the federal funds interest rate is near zero, but Fed policymakers anticipate that the neutral nominal rate of the federal funds rate in 2024 will be in the neighborhood of 2.5%. This isn’t a prediction or rigorous calculation of the average interest rate of federal debt, just a ballpark illustration of the kind of increase that may be called for in the future.

So, facing the prospect of such increases, politicians may have an intense desire to suppress interest costs and liquidate (that is, reduce) the real value of public debt, rather than raise taxes or cut expenditures. This they can do through defaults (including forced restructuring), financial repression, and inflation. Presuming that defaulting on the debt is off the table, that leaves financial repression and inflation.

TOOLS USED TO EASE GOVERNMENT’S FISCAL BURDEN OF PUBLIC DEBT

Minimizing debt costs can be done through acts of financial repression—that is to say, limiting or capping interest rates, capturing a pool of domestic capital, or direct control over parts of the financial industry.

Limits on Interest Rates can be imposed on government debt and can be either explicit or indirect. However, they are not necessarily confined to government debt. Examples include:

- Capping rates that depository institutions are allowed to pay on demand deposits and savings deposits.

- Placing upper limits on bank lending rates, particularly to government-favored borrowers.

- Central bank maintenance of interest rate targets (or equivalently, government bond prices), particularly on marketable government-issued debt securities.

Capturing a Pool of Domestic Capital that is encouraged or compelled to direct credit to the government artificially increases the demand for government debt and so lowers its interest cost. This is typically achieved through regulations or tax measures. Some examples include:

- Foreign exchange controls and/or restrictions on investment abroad.

- Restrictions or prohibitions on transactions in precious metals, particularly gold.

- Requiring depository institutions to hold inordinately high levels of reserves on which no interest is paid.

- The imposition of so-called “prudential” regulations, like requiring domestic financial institutions (banks, insurance companies, pension funds—particularly public pension funds) to hold specified amounts of government debt in their portfolios.

- Taxes on securities transactions other than government debt— particularly equities.

Direct Control Over Segments of the Financial Industry. Examples include:

- Government ownership (or management control) of banks or other large financial institutions.

- High barriers to entry into the financial industry through regulation.

- Directing financial institutions to provide credit to specified industries/companies, such as government-owned enterprises or “national champions.”

- Public-debt burden being reduced by initiating, tolerating or accelerating inflation. Inflation reduces the real value of government debt—increasing the nominal amount of GDP (and tax revenues) but not the interest rate paid, except of course, for inflation-indexed bonds, which are typically only a small portion of overall government debt.

The United States has previously used both inflation and financial repression to ease the government’s fiscal burden of public debt.

As a result of WWII financing needs, public debt topped 106% of GDP at the end of fiscal year 1946. It is often claimed that the debt to GDP ratio was subsequently reduced largely through economic growth—that is, raising GDP. It’s true that economic growth eventually played a role, longer term. However, that was not initially the case.

During the war, the U.S. Treasury Department set a specific structure of returns for Treasury securities with the longest issues capped at 2.5%. The Fed engaged in open market operations to keep Treasury bond prices at par.

Immediately after the war, interest rates were still suppressed, but inflation was high: 8.3% in 1946, 14.4% in 1947, and 8.1% in 1948, effectively reducing the real value of public debt by roughly a third during that period.

And the level of nominal debt was lowered from $241.9 billion at the end of fiscal year 1946 to $214.3 billion by the end of fiscal year 1951. Low interest rates were maintained with the Fed effectively subordinate to the Treasury until the Fed-Treasury accord of March 1951.

As it turned out public debt relative to GDP fell considerably between the end of WWII and the 1970s. An important factor behind the drop was that the growth rate of nominal GDP was higher than the interest rate on government debt most of the time.

From 1945 to 1980, binding interest rates on deposits kept real deposit rates deeper in negative territory than government bonds. The effective real interest rate on U.S. government debt was below 2% about 85% of the time, below 1% about 55% of the time, and 0% about 50% of the time.

It’s interesting to note that government authorities are often reluctant to give up any measure of control over anything. So individual elements of financial repression tend to continue after their stated rationales have ceased to exist. For example:

- Reg Q (caps on bank deposit rates) lasted from the Great Depression through 1986.

- The prohibition on ownership of gold was in place from 1933 through 1974.

- An interest rate equalization tax applied on foreign securities incomes from 1963 through the mid-1970s.

MITIGATING THE IMPACT OF FINANCIAL REPRESSION AND INFLATION

So, where are we? It’s not the most likely, but in a worst-case scenario, continued highly expansionary fiscal and monetary policies have the potential to create highly inflationary conditions. However, these probably wouldn’t rise to the surface prior to 2024.

If they do, the effects will be one or more of accelerating inflation, higher interest rates, and financial repression. The magnitude of any the effects will depend on the economic and the political climate at that time.

There are actions investors can take to mitigate the impact of financial repression and inflation. AMG will be monitoring the financial and political landscape to assess the risks of such potential developments and advise our clients accordingly. Actions could include making investments in:

- Foreign currency denominated assets in offshore locations where financial repression is minimal.

- Precious metals.

- Assets that can be readily leveraged (e.g. real estate) and where high amounts of long-term debt at fixed interest rates may be obtained that are non-recourse to the borrower.

- Various tailor-made private equity programs.

- Real assets in general.

“We’re not saying this is the likelihood,” AMG’s Wright said. “We’re saying that if things in 2024 start looking like (the 1970s) … fiscal policies continue to be aggressive and the Federal Reserve doesn’t look it has the answers to what’s going on in the money supply arena, we have to prepared for that.

“We’ve been at this rodeo before, we know what it is, and we’ll be prepared to handle it.

This information is for general information use only. It is not tailored to any specific situation, is not intended to be investment, tax, financial, legal, or other advice and should not be relied on as such. AMG’s opinions are subject to change without notice, and this report may not be updated to reflect changes in opinion. Forecasts, estimates, and certain other information contained herein are based on proprietary research and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any particular security, strategy, or investment product.