Consumer Spending Shortfall During a Pandemic

• 12 min read

Get the latest in Research & Insights

Sign up to receive a weekly email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Consumer spending is the engine of the U.S. economy, representing over two-thirds of the total U.S. GDP. The level of U.S. consumer spending is determined by disposable personal income, or how much money households make after taxes, and personal savings, or how much income households choose to save versus spend.

Wages from employment, the main driver of disposable personal income for most households, declined significantly in March and April 2020 as over 22 million Americans lost their jobs in the wake of COVID-19-related shutdowns. Without support from the federal government, U.S. consumers would have lost an estimated $1 trillion in annualized disposable personal income over those two months.

In response, Congress passed the CARES Act in March 2020, which included extensions to state unemployment benefits, direct payments to individuals, and support for businesses. The Act provided a historic boost to U.S. disposable personal income. However, consumer spending has remained depressed due to low consumer confidence, limitations on where consumers can spend their money, and fears surrounding potential long-term damage to the U.S. labor market. As a consequence, forecasts for consumer spending and economic output over the next two years remain well below pre-pandemic expectations.

Given the longer-term risks to the U.S. economy, additional fiscal stimulus from the federal government may be appropriate.

We consider three potential scenarios for the direction of U.S. personal savings and estimate the amount of net effective stimulus, or stimulus that reaches U.S. disposable personal income, needed to return consumer spending to pre-COVID-19 levels by mid-2021.

The results of the analysis suggest that net stimulus to disposable personal income of between $333 billion and $534 billion through June 2021 may be sufficient to return U.S. consumer spending to pre-COVID-19 levels. These amounts represent 42% to 68% of the existing net effective stimulus provided by the CARES Act.

Further, the primary forms of personal income stimulus being discussed by Congress, payments to individuals and expanded unemployment benefits, could serve to support the existing spending of lower-income U.S. households while encouraging greater spending from higher-income households.

Overall, additional stimulus from the federal government in line with the policies and amounts discussed in this paper could provide U.S. consumer spending with a much-needed boost and should help strengthen the U.S. economic recovery.

CONSUMER SPENDING DRIVES THE U.S. ECONOMY

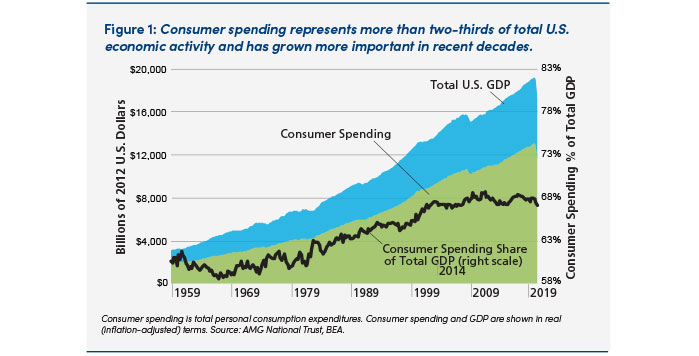

As the United States imposed lockdowns and public restrictions to slow the spread of COVID-19 in early 2020, economists began estimating both the short term and longer-lasting impacts to the U.S. economy. While the shuttering of businesses and declines in manufacturing output have a measurable impact, the largest component of U.S. economic output, as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP), is consumer spending.

Consumer spending, officially referred to as personal consumption expenditures by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), includes individual spending on everything from food to rent to automobiles. As of the second quarter of 2020, consumer spending constituted over 67% of total U.S. GDP, a share that has risen significantly since the 1960s (Figure 1).

COVID-19’S IMPACT ON THE U.S. ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

U.S. consumer spending is determined by disposable personal income, or how much money households make after taxes, and personal savings, or how much income households choose to save rather than spend.

For most households, the primary driver of disposable personal income is wages from employment. Between February and April 2020, over 22 million Americans lost their jobs as pandemic-related lockdowns closed businesses and restricted consumer activity.1 Without support from the federal government, U.S. consumers would have lost an estimated $1 trillion in annualized disposable personal income over that two month period.2

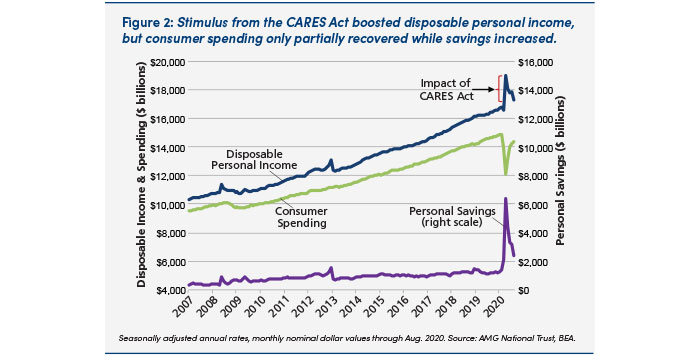

In order to protect the U.S. economy from the unprecedented impact of COVID-19, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act in March 2020. The CARES Act provided $2.2 trillion in funding for extensions to state unemployment benefits, direct payments to individuals, funding for state and local governments, and loans, grants, and tax breaks for U.S. businesses, among other programs.3

The Act provided a historic boost to the disposable personal income of U.S. households. Consumer spending has been restrained, however, as consumers pulled back on purchases and have been less able to spend in places like hotels, restaurants, and retail stores. As a result, household savings grew during the shutdown (Figure 2).

U.S. households have been padding their savings for a variety of reasons. As of September 2020, U.S. consumer confidence remained at its lowest level since 2013,4 causing households to set aside funds for spending in an uncertain future. Further, nearly half of workers who lost their jobs since the pandemic began no longer expect to return to their original jobs.5 This is in line with a study on U.S. small businesses that concluded 42% of COVID-19-related job losses may become permanent.

In addition, when the portion of the CARES Act that provided companies loans to keep workers on payroll (Paycheck Protection Program) ended in early August, an estimated 22% of small businesses participating in the program were forced to lay off employees.7 Large employers such as airlines have also laid off tens of thousands of employees as federal support for the airline industry expired and have warned that, absent additional fiscal support, further layoffs are likely.8

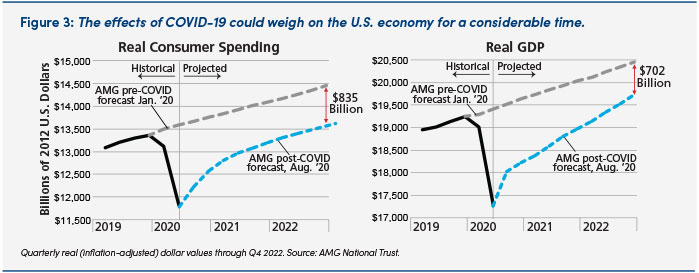

Left unaddressed, such structural changes could cause long-term scarring to the productivity of the U.S. labor force and consumer financial health, which could be a drag on economic activity over decades to come. AMG’s forecasts for U.S. consumer spending and GDP over the next two years, for example, remain well below pre-pandemic expectations (Figure 3).

ESTIMATING THE AMOUNT OF NET EFFECTIVE STIMULUS NEEDED TO RETURN CONSUMER SPENDING TO PRE-COVID-19 LEVELS

Given the longer-term risks to the U.S. economy due to COVID-19, additional fiscal stimulus, or spending by the federal government to increase economic activity, may be appropriate.9,10

Using assumptions about the direction of disposable personal income excluding fiscal support,11 this analysis estimates the amount of net stimulus, or stimulus that reaches disposable personal income, that will likely be required if U.S. consumer spending is to return to pre-COVID-19 (January 2020) levels by June 2021.

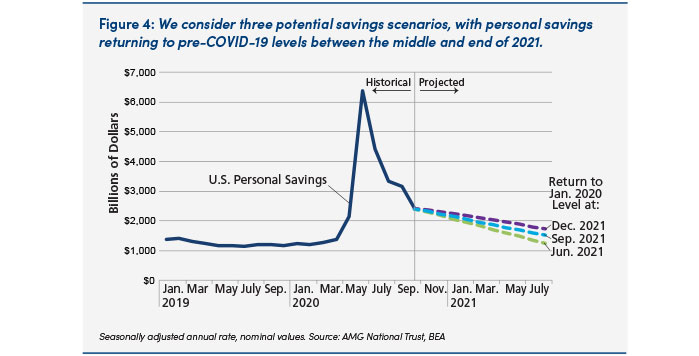

Although total U.S. personal savings have declined significantly from the high reached in April 2020, they remain well above where they were prior to the pandemic. Further, the progress of savings back to pre-pandemic levels is expected to slow going forward amidst ongoing economic uncertainties and as households are increasingly forced to dip into their savings to cover current expenses. AMG’s estimates consider three savings scenarios, with personal savings returning to January 2020 levels by either June 2021, September 2021, or December 2021 (Figure 4).

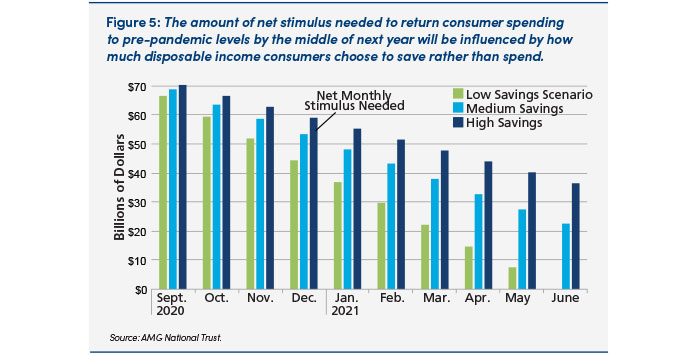

Under the June 2021 recovery, or “Low Savings” scenario, an average of $33 billion per month in net federal stimulus may be needed between September 2020 and June 2021 to return U.S. consumer spending to pre-COVID-19 levels. In the “Medium Savings” and “High Savings” scenarios, an average of $46 billion and $53 billion in net monthly stimulus, respectively, could be required.

In all three scenarios, the necessary monthly stimulus amount would decrease as savings rates decline and consumers spend a larger portion of their disposable personal incomes (Figure 5).

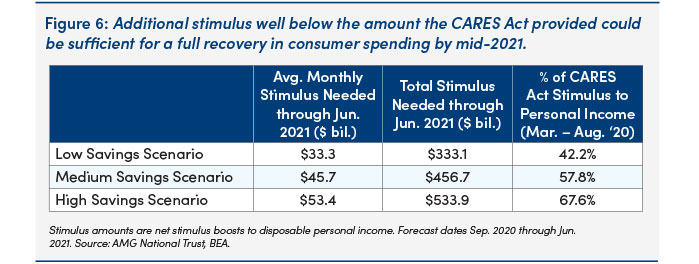

In total, the amount of stimulus that would need to reach U.S. disposable personal income through the middle of next year under the Low, Medium, and High Savings scenarios is $333 billion, $457 billion, and $534 billion, respectively. These amounts of net stimulus would likely help return aggregate U.S. consumer spending to near-January 2020 levels by June 2021.

Compared to the existing stimulus from the CARES Act, the additional net stimulus required for a rebound in U.S. consumer spending would likely be relatively modest. The CARES Act provided an estimated $790 billion to U.S. disposable personal income between March and August 2020,12 so the necessary stimulus to disposable income going forward represents just 42% to 68% of the amounts already provided (Figure 6).

HOW PUBLIC POLICY COULD HELP SUPPORT THE RECOVERY

Any aggregate fiscal stimulus package will likely be much larger than the amounts discussed here, as funding will probably also include support for small businesses, hard-hit industries, and state and local governments, among others.13 In terms of provisions that directly boost disposable personal income, however, the two policies Congress has focused on are expanded unemployment benefits and direct payments to individuals.

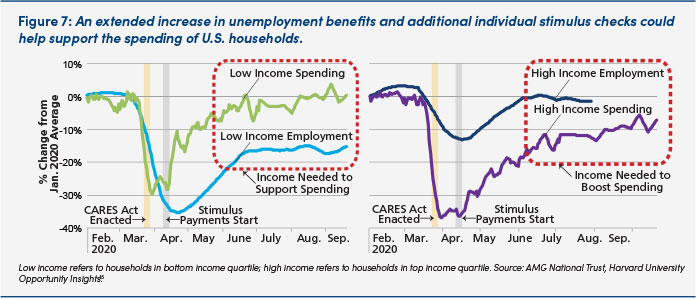

These types of stimulus measures affect Americans differently depending on their household incomes. After CARES stimulus payments began in mid-April 2020, for example, spending for lower-income households quickly recovered to pre-COVID-19 levels. Part of the reason is that lower-income households typically spend most of their budgets on necessary items like food and shelter, rather than nonessential items they can elect not to purchase. Additionally, the expanded unemployment benefits and individual payments provided by the CARES Act represented a much larger relative income boost for lower-income households than they did for higher-income households.

Job losses for lower-income households in the wake of COVID-19 were also much larger than they were for higher-income households. This was due to pandemic shutdowns disproportionately impacting low-wage jobs in the leisure, hospitality, retail, and foodservice industries.14 With employment in these heavily impacted industries remaining depressed, additional income from expanded unemployment policies and individual payments provides an important source of support for the spending of lower-income families.

Households with higher incomes experienced far fewer job losses after the pandemic shutdowns began, but experienced an even greater decrease in total spending. This again is due to the fact that higher-income households spend a much greater share of their total income on nonessential items and services, the supply of which has been constrained by social distancing and capacity limitations. Nonessential spending also depends more heavily on healthy levels of consumer confidence.

Ultimately, while expanded unemployment benefits and individual stimulus payments from the CARES Act appeared to contribute to a rebound in spending amongst higher-income families, more may be needed to return total spending to pre-pandemic levels (Figure 7).

BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER

AMG’s findings suggest that additional stimulus policies similar to those Congress has previously enacted could help U.S. consumer spending and total economic output recover to pre-COVID-19 levels more quickly.

The amount of additional stimulus to disposable personal income needed to return U.S. consumer spending to pre-pandemic levels by the mid-2021 is likely much lower than what was already provided by the CARES Act. Overall, any additional stimulus from the federal government in line with the policies and amounts discussed in this paper could provide U.S. consumer spending and the broader economy with a much-needed boost and should help strengthen the U.S. economic recovery.

For more insight on AMG’s economic, public policy, and investment research, please visit our Research & Insights page or contact an AMG advisor.

Notes

- Based on monthly total nonfarm payrolls as reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

- Change in seasonally adjusted annualized disposable personal income excluding CARES Act stimulus provided to disposable personal income between Feb. and Apr. 2020, as reported by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). bea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-10/effects-of-selected-federal-pandemic-response-programs-on-personal-income-august-2020.pdf.

- United States Congress. Public Law 116-136, Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. Congress.gov, congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748.

- University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index. Surveys of Consumers. University of Michigan, sca.isr.umich.edu.

- Boak, Josh, and Emily Swanson. “AP-NORC Poll: Nearly Half Say Job Lost to Virus Won’t Return.” AP NEWS, Associated Press & University of Chicago National Opinion Research Center, 24 Jul. 2020, apnews.com/ba6ea32e7a5ee4b79c7aed945e4d25b7.

- Barrero, Jose Maria, et al. “COVID-19 Is Also a Reallocation Shock.” NBER Working Paper No. 27137, National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2020, nber.org/papers/w27137.

- “Covid-19 Small Business Survey.” National Federation of Independent Business, NFIB Research Center, 10 July 2020, assets.nfib.com/nfibcom/FINAL-Covid-19-9-Write-up-and-Questionnaire.pdf.

- Schlangenstein, Mary, and Saleha Mohsin. Airlines Near 50,000 Job Cuts as American, United Feel Squeeze. Bloomberg, 30 Sept. 2020, bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-09-30/airlines-near-50-000-job-cuts-as-american-united-feel-squeeze.

- Hansen, Sarah. Mnuchin Says More Stimulus Needed-Don’t Worry About The Deficit. Forbes Magazine, 14 Sept. 2020, forbes.com/sites/sarahhansen/2020/09/14/mnuchin-says-more-stimulus-needed-dont-worry-about-the-deficit/.

- Powell, Jerome. “Testimony by Chair Powell on Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 22 Sept. 2020, federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/powell20200922a.htm.

- Analysis assumes nominal consumer spending, disposable personal income excluding fiscal stimulus, and personal interest and transfer payments return to Jan. 2020 levels by Jun. 2021. Nominal personal savings are assumed to return to Jan. 2020 levels by either Jun. 2021, Sep. 2021, or Dec. 2021. All monthly changes between current levels and expected future levels are linear extrapolations.

Required stimulus to disposable personal income is calculated as the difference between (forecasted consumer spending + personal savings + interest payments) and the forecasted disposable personal income excluding fiscal stimulus. The seasonally adjusted annual values are converted to monthly values by dividing by 12, and then summed over the period from Sep. 2020 to Jun. 2021. - Sum of monthly amounts from Mar. to Aug. 2020, converted from the seasonally adjusted annual rates reported by the BEA (see endnote 2).

- United States Congress, House. The Heroes Act. Congress.gov, congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/8406/text. 116th Congress, House Resolution 8406, introduced 29 Sep. 2020.

- Kinder, Molly, and Martha Ross. Reopening America: Low-Wage Workers Have Suffered Badly from COVID-19 so Policymakers Should Focus on Equity. The Brookings Institution, 23 June 2020, brookings.edu/research/reopening-america-low-wage-workers-have-suffered-badly-from-covid-19-so-policymakers-should-focus-on-equity.

- Spending data from Affinity Solutions. Employment data and data compilation by Harvard University Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker. The Economic Tracker. Harvard University Opportunity Insights, tracktherecovery.org.

This information is for general information use only. It is not tailored to any specific situation, is not intended to be investment, tax, financial, legal, or other advice and should not be relied on as such. AMG’s opinions are subject to change without notice, and this report may not be updated to reflect changes in opinion. Forecasts, estimates, and certain other information contained herein are based on proprietary research and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any particular security, strategy, or investment product.

Get the latest in Research & Insights

Sign up to receive a weekly email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.