The Inflationary Ripples of Russia’s War

• 4 min read

Get the latest in Research & Insights

Sign up to receive a weekly email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.

Simply stated, the first quarter of 2022 was dreadful timing for a supply-side shock to rattle global economies.

Right as the output gap closed—even turned positive in some instances—across many advanced nations and elevated inflation was showing signs of peaking, Russia invaded Ukraine and threw a monkey-wrench into the economic recoveries.

When economies operate below their capacity and unused resources lay dormant—as was the case for many months after the COVID-19 outbreak—elevated inflation can coexist with robust growth without rapidly seeping into expectations of future inflation.

This calculus changes, however, once the output gap closes and an economy’s productive capacity acts as a constraint. Price spikes are more likely to stick and become a newly expected normal.

The Russian invasion occurred right when major economies—including the United States—were transitioning from operating below capacity to running possibly “too hot.”

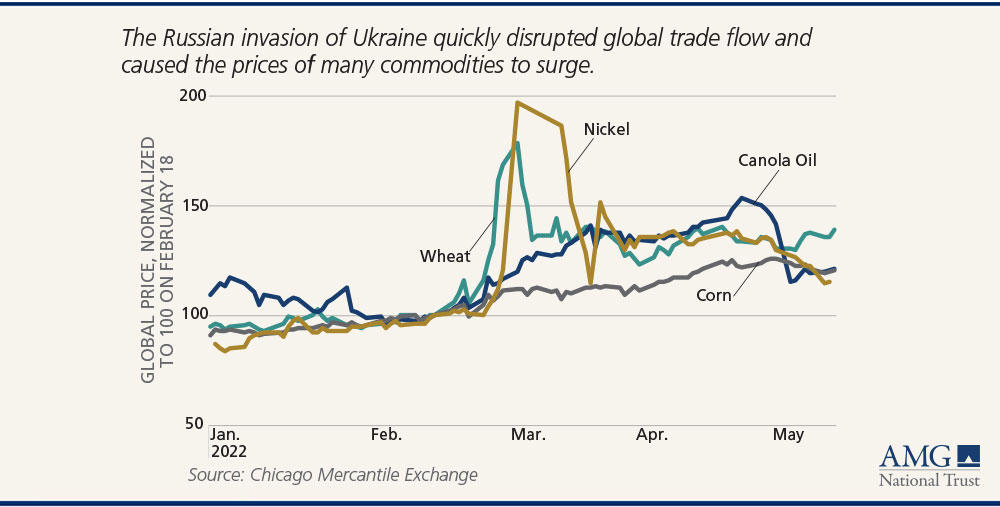

At first glance, even the combined footprint of Russia and Ukraine on the global economic stage does not appear significant, certainly not in terms of direct links to the domestic economy. Measured by total trade (annual imports plus exports) neither nation ranked among the top 15 trade partners for the United States. But the consequent rapid runup in global prices for many commodities sent far-reaching ripples beyond rising energy prices.

Great(er) Expectations

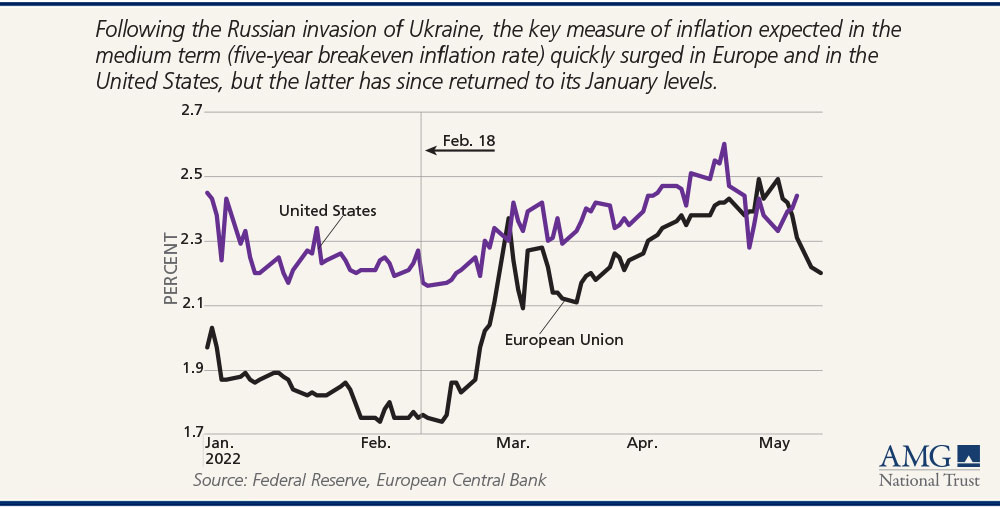

For sobering evidence of the conflict’s economic fallout look no further than global inflation expectations. By distilling implied future inflation rates from an array of traded instruments, including Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) and interest-rate swaps, AMG estimated the discreet step-up that occurred shortly after the late-February invasion.

In late January the expected rate of inflation over the next year in the United States was 3.5%. On March 15 it stood at 5.4%.

The shudder was even worse in the Euro Area, where heavy reliance on Russian energy supplies means European manufacturers face soaring energy costs in addition to disrupted trade with Russia. Inflation expectations in the Euro Area have therefore seen an even steeper trajectory than the United States. The one-year inflation swap rate rose to 5.9% on March 8.

How Can Two Emerging Economies Whiplash the Rest of the World?

First, the unfortunate timing: a smaller output gap means less buffer was available during the first quarter to absorb price shocks. Surging prices on everything from fertilizer to nickel directly added to inflation worldwide.

Second, Russian and Ukrainian seafarers make up one-seventh of the global shipping workforce and are often staffed as officers vital for vessel operations. Sanctions disrupted freight firms’ ability to pay salaries into some foreign bank accounts and rerouted air traffic impaired many sailors’ ability to report for duty. The resulting fallout to global supply chains that have not fully recovered from COVID-19 disruptions will delay the timing of “peak” post-COVID-19 inflation.

Third, Russia and Ukraine account for 12.0% of all exported calories globally and the war will significantly disrupt this production capacity. Global food prices—which were accelerating even before the war—will now spiral faster.

Global Prices for Select Commodities

Near-term inflation pressures have certainly worsened, but there is reason for cautious optimism beyond the next six months.

Commodity prices today will not necessarily feed through into lofty inflation in the longer run. A substantive body of research shows that the pass-through from higher energy prices into non-energy domestic inflation—especially core inflation—is relatively muted.

That helps explain why market expectations of longer-term price trends did not move in direct lockstep with near-term swings: pricing for inflation five years from now did not surge on the same order as near-term rates.

Expected Inflation Rate Five Years From Now

Monetary Policy Is Now More Difficult

The Federal Reserve and European Central Bank have been gearing up for tighter monetary policy, but the Russo-Ukrainian war will make this an even tougher job. Fortunately, central banks’ hands are not tied, and their policy trajectories not set in stone. Although the received wisdom of past decades is that policymakers should avoid over-tightening in the face of supply-side shocks, the unique characteristics of post-COVID-19 recovery grant leeway and encourage flexibility.

Wars are inherently unpredictable, and the path forward is likely to be messier than any stylized scenarios. A sanguine long-term outlook could be quickly scuttled if Russia cuts off Europe’s gas supply triggering a localized recession, just as the United States experiences significantly tighter financial conditions, a bigger hit to growth, and a Federal Reserve that would need to reconsider the speed of its expected tightening.

This article is based on data released as of May 18, 2022.

To receive a full copy of the Executive Summary or the entire 24-page “Notes on the Economy” report, contact your AMG advisor or submit a request for more information.

This information is for general information use only. It is not tailored to any specific situation, is not intended to be investment, tax, financial, legal, or other advice and should not be relied on as such. AMG’s opinions are subject to change without notice, and this report may not be updated to reflect changes in opinion. Forecasts, estimates, and certain other information contained herein are based on proprietary research and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any particular security, strategy, or investment product.

Get the latest in Research & Insights

Sign up to receive a weekly email summary of new articles posted to AMG Research & Insights.